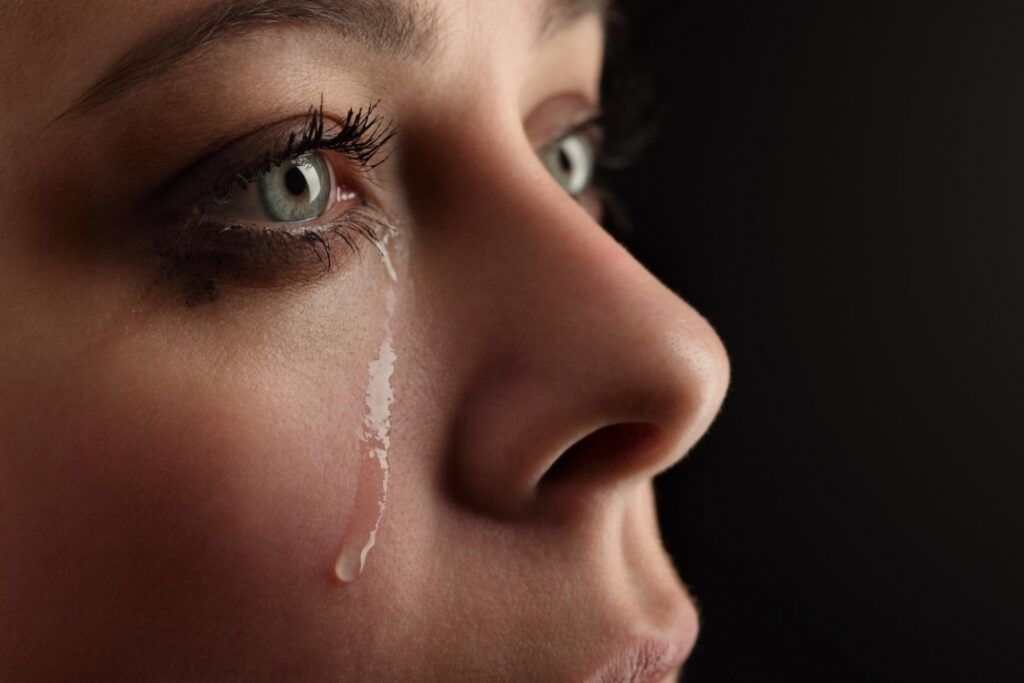

We are a nation in mourning. In February, we passed the landmark of 500,000 deaths in the U.S. due to the effects of COVID-19. That’s half a million people who died. Add to that the nearly three million people who died of other causes over the past year. Those are staggering statistics, but they aren’t the whole picture. In addition to our grief for loved ones who have died, we are grieving for a way of life. We grieve for the ability to gather with groups of friends, family or even strangers to collectively celebrate special occasions, to console each other, to be entertained, to be educate, and to just enjoy being together. We grieve for the traditions we could not practice or that were changed so much they were barely recognizable. We grieve for the sense of safety and ease with which we used to be able to move about in our daily lives and in our communities. We grieve for the lives that were taken because of the color of their skin. We grieve for the loss of our national self-image as a democracy sustained through the peaceful transition of power. We grieve for the failure of daily life to measure up to our expectations of how it should be.

Just as loss is a part of life, grief is a part of life – but the grief we are experiencing now is not ordinary grief. It is complex, compounded by the multiple layers of loss we have experienced over the past year. Our grief has been de-legitimized by political and cultural leaders who tell us that its causes are a hoax, that COVID-19 is no worse than “a bad flu” and restrictions unnecessary. Our grief is simultaneously intensified and de-legitimized every time that a review board or jury determines makes an official decision that the use of deadly violence was “justifiable.” It is prolonged grief as we don’t yet know when the losses will stop.

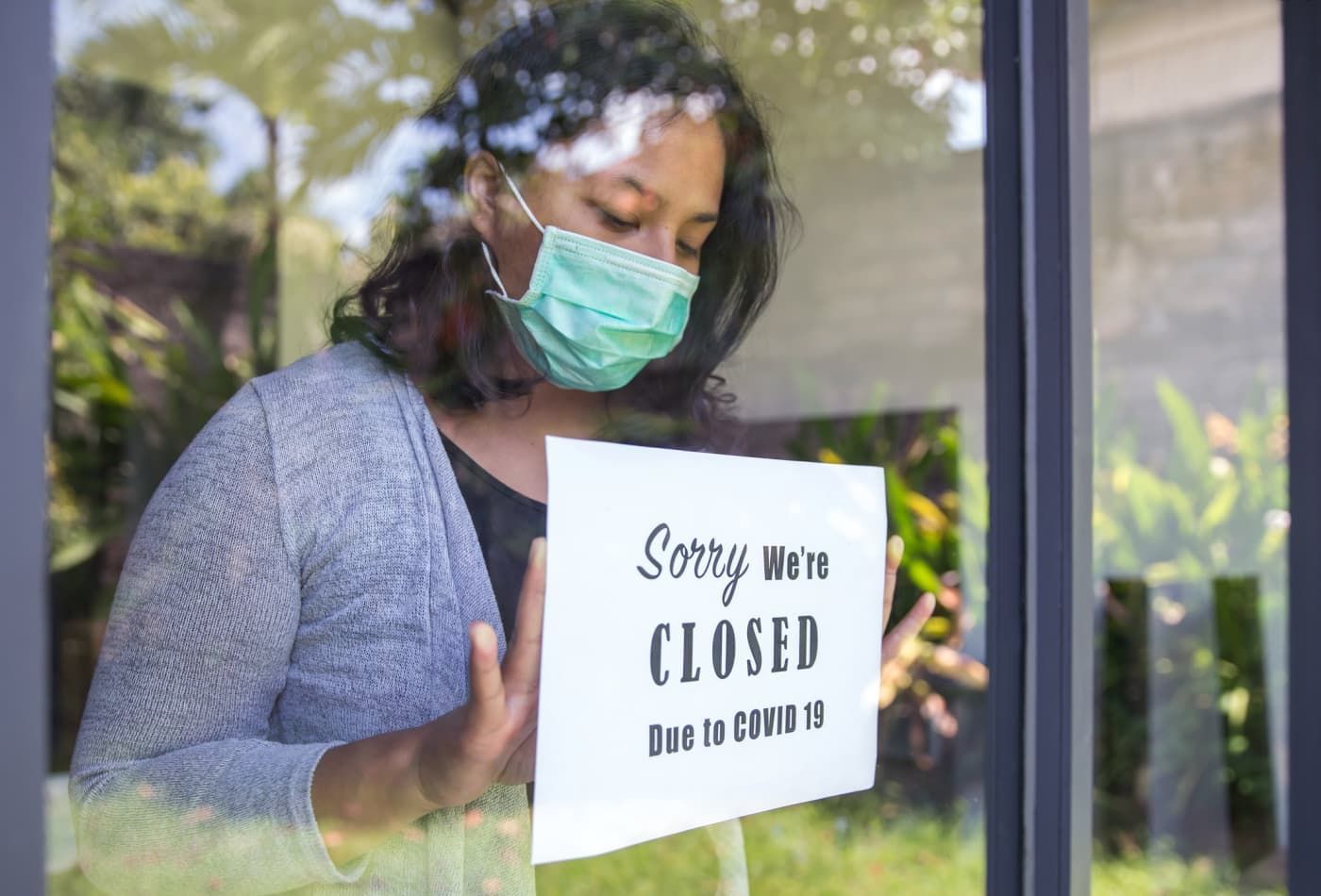

Those of us who have not experienced a “big” loss such as the death of a loved one or having to close down a business that couldn’t sustain itself, might feel a little shame at times for how upset we were over not being able to take the trip we wanted or to throw a big party. These disappointments seem trivial by comparison but are nonetheless losses. The cumulative effect of all the cancellations, indefinite postponements, and other disappointments weighs us down with a heavy sense of weariness.

Grief experts tell us that the first task of mourning is to accept the reality of the loss. In normal times, we have cultural traditions, such as funerals, that help us to confront the reality of a loss. But these aren’t normal times. For the past year, many of us have not been able to participate in these rituals. Due to health-related restrictions, funerals have been restricted to only the closest friends and family. Other losses that we’ve experienced don’t readily come with a ritual or ceremony for recognizing the loss.

It is not unusual for a person in the early stages of mourning to experience a sense of non-reality about the loss. We might have thoughts that there must have been a mistake, it couldn’t be true that this happened. The non-reality shows up in those brief lapses of memory when we go to share our good news with our loved one before remembering that we can’t because they aren’t here anymore. It sometimes tricks us into seeing random strangers on the street and thinking we recognize them as our loved one who died. This same sense of non-reality, coupled with the relative invisibility of the virus itself, is what leads us to a false sense that maybe the risk isn’t as bad as the officials say it is.

We must accept the reality of the losses that we’ve suffered and allow ourselves to grieve for those losses. By recognizing that we are in mourning, we help ourselves to have a context for understanding what we are experiencing and to have compassion for those around us who are mourning their own losses.

Every day you hear people talking about their eagerness and impatience to “get back to normal.” This is another common grief reaction. It is natural to want to feel normal again. Change pushes us out of our comfort zones. Some changes (ones that are wanted or ones that come in small enough doses) are relatively easy to adapt to; others are more jolting.

As more people get vaccinated, as restrictions are lifted, and as schools and businesses reopen, we need to recognize that we won’t be returning to life exactly as it used to be. We can’t just pick up where we left off before COVID-19 came into our lives. Loved ones who died are not going to come back.

Every day you hear people talking about their eagerness and impatience to “get back to normal.” This is another common grief reaction. It is natural to want to feel normal again. Change pushes us out of our comfort zones. Some changes (ones that are wanted or ones that come in small enough doses) are relatively easy to adapt to; others are more jolting.

As more people get vaccinated, as restrictions are lifted, and as schools and businesses reopen, we need to recognize that we won’t be returning to life exactly as it used to be. We can’t just pick up where we left off before COVID-19 came into our lives. Loved ones who died are not going to come back.

ACKNOWLEDGE AND ACCEPT THE LOSS(ES)

We must start by recognizing that a loss has occurred and that the loss is permanent. This sounds a whole lot simpler than it is. Some of the losses are more obvious than others. Some of the losses don’t feel as real because we haven’t experienced the full impact of the change yet. Acceptance can wax and wane over time; that’s normal.

RECOGNIZE THAT ALL LOSSES ARE THE SAME AND EVERYONE DOESN'T GRIEVE IN SAME WAY

Because there have been so many losses over the past year, it is likely that you are not the only person you know who is mourning. Many people have experienced multiple losses. It is neither healthy nor helpful to compare grief. Just because someone is not reacting the same way as you or doing the same things as you to cope, doesn’t mean they aren’t doing it right. What helps for one person may not help for another. If someone you know needs to tell you about a loss they’ve experienced, listen. Don’t assume you know what they’re going through just because you’ve been through a similar loss.

ALLOW YOURSELF TO FEEL WHATEVER YOU ARE FEELING

If you need to cry, cry. If you don’t, don’t. Whatever emotional reaction you have is legitimate and okay to express. It is not healthy to “put up a good front” and bottle up feelings. Emotions are not a sign of weakness, they’re a reflection of love. Jamie Anderson, the author of Doctor Who, wrote “Grief, I’ve learned, is really just love. It’s all the love you want to give but cannot. All of that unspent love gathers up in the corners of your eyes, the lump in your throat and in that hollow part of your chest. Grief is just love with no place to go.”

LEARN TO ADJUST TO A NEW REALITY

A lot has changed over the past year and we need to figure out ways to adjust to the new circumstances of our lives. That may mean a lot of different things. It may mean we need to develop new skills so that we can be better prepared to take on the tasks that lie ahead for us. It may mean that we must seek out new relationships or find different ways of interacting in order to maintain relationships. It may mean that we need to think about ourselves or the world in ways that we never have before. These changes can be very difficult and will take time.

ALLOW YOURSELF THE TIME YOU NEED

Grief is not something that can be resolved in a weekend. Often the reality of the situation doesn’t even begin to sink in for quite some time. For many people, it takes a full cycle of all four seasons and all the holidays before all aspects of the loss are evident. Don’t allow anyone to pressure you to speed things up (e.g., “Aren’t you over that yet?”) if you’re not ready. Similarly, don’t let anyone hold you back when you are ready to move on.

FIND WAYS TO REMEMBER THE PAST WHILE ENGAGING WITH THE PRESENT AND FINDING HOPE FOR THE FUTURE

It is important to find ways of honoring those who have died (or are no longer actively part of our lives for other reasons). They don’t stop mattering to us or having an impact on us. We are challenged to honor their memory and the life they led without sacrificing the ability to move forward in our own lives. Our deceased loved ones would want us to be the best possible versions of ourselves and to lead healthy, fulfilling lives. If your grief is not for a person but for a way of life, the loss of a dream, the loss of a personal identity, or another form of loss, this task is still applicable. Starting a new chapter of your life does not negate the relevance of the chapters that came before. The challenge for you is to incorporate some element of those past ways, identities and dreams into your newly evolving reality. There are countless ways to do this – taking up a cause that positively impacts others, making time to pause and remember, doing something that the person would have done or in the way they would have liked, contributing to a charity or social program. It means continuing to love, to grow, to learn, to laugh and to live.

Child and Adolescent Behavioral Health's Trauma Program Mary Kreitz, LPC, CDCA, is the author of this blog. Mary is an expert in the her field with 18 years of experience. If your child or adolescent is experiencing grief and your family needs coping strategies, please contact C&A at 330-433-6075.

RECENT POSTS