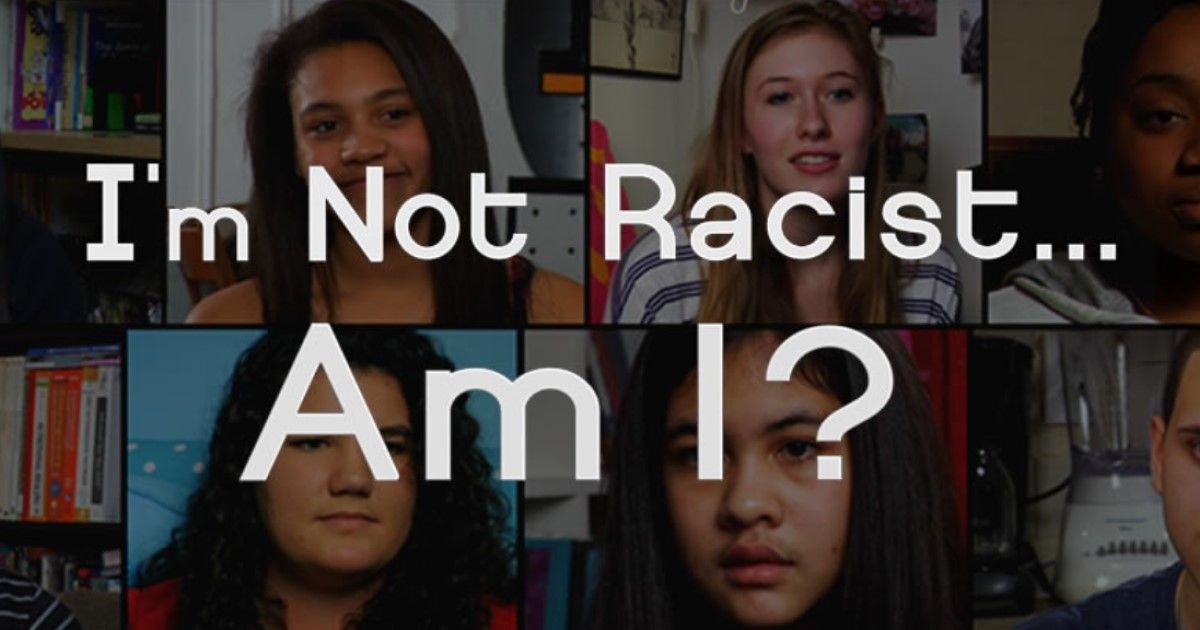

In the film, I’m Not Racist… Am I? as introduced and explored in first of this three-part blog post series, the participants engaged in multiple workshops that address race and racism. Interpersonally, the group of students grapple with their own differences and similarities, which impact the content and emotions they share with each other. There are several moments in the film that demonstrate the clear differences in the participants’ understanding of race.

In the first workshop, the students were exposed to the idea that all white people are inherently racist seeing as American society was founded on principles meant to support white people (see more on structural racism here, here, and here for further understanding). Several white students in the film became emotional during that workshop. Most students remained quiet. Following this workshop, a black student and a white student were filmed independently of each other in their own homes and discussed the workshop and what they learned with their families.

The white student discussed the differences between structural racism and bigotry with her mother and struggled to identify with the principles taught in the training. The black student stated to his mother how almost everything spoken in that workshop applied to him. The student further discussed his feelings by stating how overt racism is and yet how “subliminal” it is at the same time. How can something be so in your face and yet under your feet simultaneously? I immediately reflected on the dialectic of something being so clear and yet so vague. The film continued to grapple with student differences.

At the beginning of the film, one white male student discussed with his mother how he feels that all individuals, if they apply themselves wholeheartedly, have the same chance of success regardless of their skin, gender, sexuality or other demographic factors. As a white man myself, I must confess that when I was in high school, I had the same mindset. How could it be different? Especially when I was reading mythic bootstrap literature in high school classes. Sure, the harder you work the more you deserve, but that statement does not work for all Americans. I had not accounted for racial factors that inhibit the growth of others, not to mention socio-economic factors, nationalities, citizenship status, gender and age.

I continued to reflect on these statements and connected them to my experience in high school in New York City. In the wake of the Black Lives Matter movement responding to the murder of George Floyd, multiple private progressive schools in New York, including the one I went to, suffered scrutiny from students and alumni who identify as black, indigenous people of color (BIPOC). Multiple Instagram accounts surfaced with the handle “BLACK AT [school name].” I read the posts in 2020, and again before writing this post, and remembered feeling horrified knowing these acts of racism, bigotry and microaggressions happened all around me. This was subliminal to me, yet overt to others.

In one post at Calhoun, the school where I went, a student wrote: “when my friends and I were in third grade, we were late to our music class. When we first arrived at the class, our [music] teacher said, ‘why are all the brown girls late?’ The three of us had no idea what [the music teacher] meant by that because at that age, we weren’t taught about racism and the injustices against our race. At the end of the school day, our homeroom teacher [not the music teacher] had to hold us after school to explain to us what [the music teacher] meant and why it was wrong. [The homeroom teacher] was also a teacher of color.”

Another post from the Black at Calhoun Instagram states: “I have to say that the people who greeted me with the most warmth at Calhoun were always the teachers of color, the Spanish speaking kitchen ladies and the maintenance crew. They always said hello and asked me how I was doing. So many times I walked into school and felt invisible but those people made me feel real and like I mattered. What does it say about a school if the students of color feel invisible?”

At Chapin, another private progressive school in New York City, one student wrote: “black kids are CONSTANTLY educating other kids because no one takes the initiative to teach them. There was no reason that I had to explain to [a peer] that it was offensive to say a slur. I’ve never asked anyone if I can say a slur before.” Another Chapin post read “For all of ninth grade, my history teacher got me and the only other black girl mixed up. I would constantly be given the other girl’s work and tests.” At both schools, students continued to reflect on their experiences of racism and how frequently the course curriculum and reading material focused on white experiences written by primarily white authors.

In talking with my peers of color, I learned that, as kids, some of my peers were anxious to bring their lunch to school, since it wasn’t the usual peanut butter and jelly. I was told that other students were anxious about sharing their name in class considering the countless times teachers mispronounced it. Having grown up in Harlem, a predominantly black neighborhood in New York City, I had a friend in high school whose white parents would not let her come see a movie with me at the Magic Johnson movie theater and requested we go to a theater on the upper east side where they lived. I had another friend tell me his mom would not let him buy or wear a hoodie, since, as a black boy, he was at risk of being a target on the street.

As I reflect on these experiences and remember the adolescents in I’m Not Racist… Am I?, I thought about how none of these experiences were relevant to my childhood. I never had to think about what I brought to school for lunch, never worried a teacher would mispronounce my name, and certainly never questioned my goals in life and what expectations I could meet.

Considering the recency of these posts and the continued outcry among students of color, I thought about the students I work with at my school-based therapy location. In Northeast Ohio, students have reported ongoing racism and bigotry inflicted upon them at school (Henry, 2023; Morris, 2023), not to mention continued school segregation (Carrillo & Salhotra, 2022). Kids experience acts of racism and bigotry daily. As therapists and providers who work in schools—not to mention parents, school staff, alumni and community members—we need to be aware of how our own identities inhibit our ability to notice, understand and address these concerns among students. We are thus responsible for informing teachers, school administrators and our communities of the impacts of these experiences.

As I continue to think on my own learning and growth since high school and the growth of the students in I’m Not Racist… Am I?, I feel a sense of privilege around my whiteness both individually and structurally. I am reminded of James Baldwin’s essay, The Fire Next Time, where he discusses the role of whiteness, how whiteness should not be the standard to live up to, and the need for personal education and awareness to increase liberation for all. Baldwin states: “White people cannot, in the generality, be taken as models of how to live. Rather, the white man is himself in sore need of new standards, which will release him from his confusion and place him once again in fruitful communion with the depths of his own being.” (p. 97).

For further reading and learning, please watch, listen, and read the following resources that have aided in my learning and could aid in yours.

Anderson, J (2012). Admitted, but left out. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2012/10/21/nyregion/for-minority-students-at-elite-new-york-private-schools-admittance-doesnt-bring-acceptance.html

Bailey, Z. D., Feldman, J. M., & Bassett, M. T. (2021). How structural racism works—racist policies as a root cause of US racial health inequities. New England Journal of Medicine, 384(8), 768-773.

Baldwin, J (1963). The Fire Next Time.

Black at Calhoun [@blackatcalhoun]. (2020, June 17). “When my friends and I were in third grade [Photograph]. Instagram.

Black at Calhoun [@blackatcalhoun]. (2020, June 17). “I have to say that the people who greeted me [Photograph]. Instagram.

Black at Chapin [@blackatchapin]. (2020, June 29). “Black kids are CONSTANTLY educating other kids [Photograph]. Instagram.

Black at Chapin [@blackatchapin]. (2020, June 22). “For all of 9th grade, my history teacher got me and [Photograph]. Instagram.

Carrillo, S., Salhotra, P (2022, July 14). The U.S. student population is more diverse, but schools are still highly segregated. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2022/07/14/1111060299/school-segregation-report

Center for Prevention MN. (2021, January 26). What is structural racism? [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ZllrF9EB-lY

Choices Program (2020, January 28). What is Structural Racism? [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rGY1EXgYD9g

Henry, M (2023, August 8). New Ohio Black Student Equity report campus sheds lights on discrimination, campus policing. Ohio Capital Journal.

https://ohiocapitaljournal.com/2023/08/28/new-ohio-black-student-equity-report-campus-sheds-lights-on-discrimination-campus-policing/

Joffe-Walt, C., Snyder, J., Koenig S., Drumming N., Glass I., Ewing E. L., Lissy, R., Nelson S. (2022, July 26). Introducing: Nice White Parents. A new five-part series about building a better school system, and what gets in the way. New Episodes of “Nice White Parents” are available here, brought to you by Serial Productions and The New York Times. The New York Times.

McIntosh, P. (1989, July/August). White Privilege: Unpacking the Invisible Knapsack. Peace and Freedom.

Morris, C (2023, March 8). Northeast Ohio school faces charges of not addressing repeated racist incidents. WOSU Public Media.

https://news.wosu.org/2023-03-08/madison-local-schools-faces-charges-of-not-addressing-repeated-racist-incidents

Othering & Belonging Institute. (2023, January 16). Structural Racism Explained [Video]. Youtube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lQ_8eOaiz8o

C&A’s Doctoral Intern Chris Alpert presented the information for this blog post at an agency training. This is part 2 of a three-part series. In the third post, Alpert will provide reactions on C&A staff members who view the screening of I'm Not A Racist, Am I? Alpert’s doctoral internship with C&A will end on June 30, 2024. For more information regarding this topic, please reach out to C&A at 330.433.6075.

RECENT POSTS