Microaggressions are everyday slights, indignities, put-downs, and insults that people of color, women, the LGBTQ+ population and other marginalized people deal with every day. These interactions might be comments, questions or actions that send denigrating messages to people because they belong to a minority group. Microaggressions are rooted in stereotypes and reflect deeply ingrained biases that people may not be aware of having.

One of the things that makes microaggressions disconcerting is how easily they fly under the radar. Microaggressions happen casually, frequently and often without any intention of harm. In fact, the person making the comment may not even realize they are committing a microaggression.

If microaggressions are so subtle and unintentional, how do we know if we are doing them? Start by learning the forms that microaggressions can take so that you will be better able to recognize them when they happen.

Psychologist Derald Wing Sue of Columbia University has identified three types of microaggressions:

MICROINSULTS

Microinsults are messages that insult someone’s personal identity or their heritage. These can be subtle snubs, such as ignoring a black customer and serving the white customers first even though they arrived later. Another form of microinsult might actually sound like a compliment on the surface, but contain a hidden insult about a group of people. An example might be telling someone “You’re pretty for a heavy girl” or “You’re so articulate. You don’t even sound black on the phone.”

MICROASSAULTS

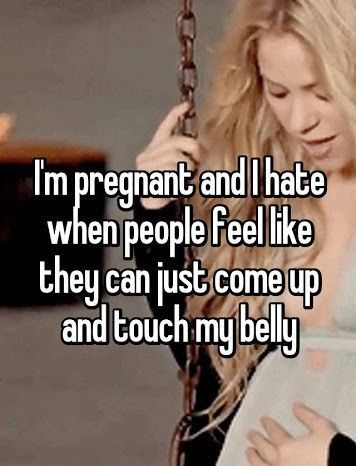

Microassaults are comments or actions that are intentionally discriminatory or intrusive. Touching a pregnant woman’s belly without permission is an example of a microassaultive behavior. Making fun of names that are unfamiliar to you or difficult for you to pronounce because they are not from your cultural background is an example of a verbal microassault.

MICROINVALIDATIONS

Microinvalidations are messages that invalidate or nullify the experience of another person. This is what is happening if someone tells you that they were insulted or offended by something Brian said and you respond, “That can’t be true. I know Brian. He’s a nice guy. I’m sure he didn’t mean it that way.” Similarly, comments like “I don’t see color” or “all lives matter” send messages that the person’s struggle as a member of a marginalized group isn’t real or that it isn’t something you care about.

An important note about the prefix “micro” needs to be made. Micro can be used to mean tiny but that’s not the meaning that applies here. Microaggressions are not tiny aggressions. Instead think of micro in the way that is used when talking about economics – we aren’t talking about things that are happening at a societal or institutional level (the “macro” level), they take place in interactions between individual persons (the “micro” level).

One of the biggest dangers of microaggression lies in its ability to be denied. A person can easily say, “that’s not what I meant” or “I was just joking.” Often the target of the microaggression gets criticized for “taking it too personally” or “being too sensitive.” The anger a person feels as a result of microaggressions might be used as evidence confirming negative stereotypes, such as “the angry black woman.” In recent years the label “snowflake” has become popular as a derogatory way to accuse someone of being overly sensitive, fragile and unable to deal with opposing opinions. It is important to recognize that intent is irrelevant in determining whether or not language or behavior is offensive. Just because you don’t intend harm when you say something doesn’t mean someone else isn’t harmed by hearing what you said.

Microaggressions do real harm. In her TEDx Oakland talk on this topic, Tiffany Alvoid explained:

“Microaggressions wound people. If we were to compare it to getting a paper cut, one paper cut is manageable but paper cuts all over your body is something quite different. And it’s the accumulation of offensive comments in social settings and professional settings that begin to take a toll on a person’s spirit.”

Research shows that microaggressions lead to lower self-esteem and higher levels stress, anger and depression in members of marginalized groups, and to uncomfortable and less productive work and educational environments.

WHAT CAN WE DO TO AVOID MAKING MICROAGGRESSIONS?

What can we do to avoid making microaggressions?There are some very basic things people can do to avoid microaggressions.

- Before you speak or act, take a moment to think, especially if you are commenting on someone’s identity.

- What could be the possible impact of what you’re about to say or do?

- How might this person react?

- Is it necessary to say this?

- Listen when people explain why certain remarks or behaviors offend them.

- Don’t be afraid to admit it when you’ve made a mistake. A single statement or behavior is not a reflection of a whole person. It is possible to make a racist comment without being a One factor that determines the difference is willingness to recognize that you’ve offended someone, apologize for the offense and learn from the experience so that the offense is not repeated.

- Make an ongoing commitment to learning.

- Seek out opportunities to learn about and interact with people who differ from you.

- Learn the meaning and history behind commonly used phrases and jokes that may be offensive.

- Strive to be aware of your own biases, the stereotypes that influence your thinking and the assumptions you make about others.

Anyone can be guilty of committing a microaggression. It doesn’t mean you are a bad person. It does mean you have some learning to do. Microaggressions are more than just insults, insensitive comments or general rude behavior. The damage they cause is real and has long-lasting effects. That’s why it is imperative that we all do our part to recognize what microaggressions are and make a conscious effort not to engage in them and not to allow them to go unchecked when we notice them happening.

Child and Adolescent Behavioral Health's Trauma Program Manager Mary Kreitz is the author of this blog post. If your child is struggling because of receiving microaggressions, please contact C&A at 330-433-6075.

RECENT POSTS