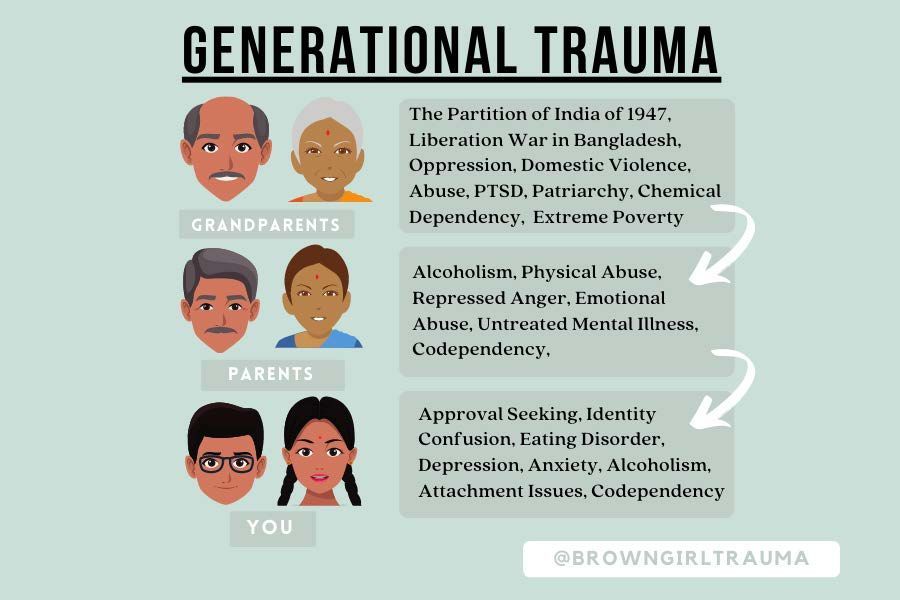

Previous blog posts in this series have looked at ways that trauma can spread across groups and cultures and ways that trauma can be passed down through generations. Today we are going to take a look at biologically-based ways that trauma can be transmitted from parent to child.

IN ULTERO EXPOSURE

When a person goes through a high stress situation there are chemical reactions that happen in the body. Of particular importance, the stress hormone cortisol is released to mobilize the resources needed to engage the fight or flight responses, should they be needed. In a typical pregnancy, the mother’s body produces a protective enzyme that regulates fetal exposure to maternal cortisol byconverting the hormone into an inactive substance before it can reach the fetus. Research has found that the bodies of some pregnant women who experienced extreme trauma produced less of this protective enzyme, thereby exposing their fetus to higher levels of cortisol in utero.

When an infant is exposed to elevated levels of stress hormones in utero, while the infant’s brain, nervous system, circulatory system, and other vital organs are still forming, it has an impact on the way those organs form. Especially if this happens over a prolonged period of time, the infant’s body becomes used to the high level of stress hormones being present. It becomes that child’s “normal” way of being. Studies of children born under types of circumstances found that the babies experienced greater distress to novelty as infants, increased impulsivity and greater difficulty organizing their thoughts during childhood, and an increased likelihood of exhibiting anxiety, behavioral disturbances, and emotional regulation problems throughout their lives.

EPIGENETICS

Epigenetics is the study of how a person’s behaviors and environment can cause changes that affect the way their genes work without changing the underlying DNA sequence. What happens is that a tag is added to the DNA molecule that acts like a dimmer switch, turning expression of a gene off or on or turning the volume of that gene up or down. These changes are thought to be heritable, meaning the tags remain in the DNA that parents pass on to their children.

Epigenetic research is still relatively new. Although researchers have shown that effects of trauma are heritable through epigenetics in animals, the connection has not yet been demonstrated empirically in humans. At this point, the connection is mainly theoretical and research is ongoing.

To understand the influence of epigenetics in trauma, let’s imagine an 18 year old black man who is driving his car and gets pulled over by the police. For almost anyone, this would be a stressful experience.

This young man, however, comes from a family in which the long history of negative experiences with police - history of police brutality against persons of color, racial profiling, “sundowner” towns, enforcement of Jim Crow laws, and patrols hunting down people attempting to escape from enslavement - has resulted in a heightened sensitivity in his autonomic nervous system. The young man sees the lights flashing and pulls over. He looks in his rearview mirror and sees the police officer get out of the cruiser and start walking toward him. The epigenetic tag on his DNA has dialed up his sensitivity to these stimuli and instead of reacting with nervousness or irritation, his brain interprets the situation as DANGER!! How does he react? Maybe he freezes and seems uncooperative. Maybe his flight instinct is triggered and he takes off. Maybe his fight instinct is triggered. Either way, the police officer sees his reaction as evidence of guilt rather than what it really is, a manifestation of multigenerational trauma.

Recognition of the multigenerational impact of trauma is very important if we want to accurately understand behavior. It isn’t enough to know what an individual has been through (though that is valuable information to know). We also need to take into consideration what happened in the history of that person’s family, and to be aware of the history of injustices and traumatic experiences that happened to others like them in the past. Knowing this information can make the difference between viewing a child as a troublemaker or viewing that child as someone who is doing the best they can to deal with difficult problems that might have begun before they were even born. By broadening our perspective, we gain a better ability to respond with compassion and empathy.

Additionally, we gain the ability to appreciate the strength and resilience it has taken for people to survive and thrive despite these challenges.

If you or someone you know is experience generational trauma, please call C&A at 330.433.6075.

* This is the second in a three-part series on Multi-generational trauma. The final segment in the series will focus on bilogical based trauma.

Mary Kreitz, LPC, CDCA has over 20 years of experience working in the field of behavioral health. She is currently the lead therapist for the Trauma Program at Child & Adolescent Behavioral Health, is a member of the Stark County Trauma and Resiliency Committee, and is a member of the Unity Coalition to Dismantle Racism in Stark County.

If you would like to support C&A services, programs or this blog, please consider making a Venmo donation to @CABehavioralHealth or use this donation link -

https://childandadolescent.org/give-to-ca/

RECENT POSTS